My cousin Georgia from Virginia vacationed with me here in Massachusetts a couple of weeks ago. By “vacation,” I mean that we explored four house museums, rambled through half a dozen gardens, and bemoaned the insanity of the world/sighed happily over the beauty of the Berkshires while rocking on the porch of the Red Lion Inn sipping gin and tonics.

When you are women of a certain age, five days of historically and botanically inspired road tripping around The Bay State is the next thing to nirvana.

We also passed an idyllic morning and unsettling afternoon at Mt. Auburn Cemetery. The latter, you might be thinking, is understandable: isn’t walking among the dead inherently unsettling?

Actually, no.

Back in the early 19th century, burying grounds in cities like Boston, Philadelphia, and New York had become as densely populated as the neighborhoods where their living souls resided. For reasons both practical (think disease) and aesthetic (think Romanticism), the rural cemetery movement was born. Visualize, as their founders did, unspoiled expanses of land several miles distant from the overcrowded, smelly, increasingly industrialized urban areas. Visualize places where the dead could be buried in their very own plots or mausoleums—no stacking of multiple bodies required. Visualize rolling hills and inviting pathways where families could visit their dead while enjoying a day out: to picnic; socialize; stroll through leafy, landscaped grounds; gaze upon the monuments, memorials, and decorative gravestones in what were essentially the nation’s first public art museums; breathe in the clean, country air.

Mt. Auburn was the first of these American rural cemeteries. Founded by members of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society on 70 acres of land in what was then the wilds of Cambridge, the now 170-acre cemetery is surrounded by busy streets and neighborhoods. Within its gated confines, however, lies a landscape of beauty, an aura of tranquility. As Supreme Court Justice and first president of Mt. Auburn Cemetery Joseph Story described it in his consecration address on September 24, 1831:

All around us there breathes a solemn calm, as if we were in the bosom of a wilderness, broken only by the breeze as it murmurs through the tops of the forest, or by the notes of the warbler pouring forth his matin or his evening song.

(This is one of the less flourishy sentences in Story’s lengthy speech. As mentioned, American Romanticism was under full steam at the time.)

The day Georgia and I visited Mt. Auburn Cemetery started out quite pleasantly, with calm and warbler notes aplenty. We gazed at gravestones, used our iPhones to identify unknown trees, flowers, and flowering trees, and wandered at will. As lunchtime approached, we came across a upscale graveside reception, complete with champagne, a buffet, and fancy hats. Georgia and I briefly considered posing as long-lost relatives of the deceased but convinced ourselves that we were better than that and opted for a meal at the nearby and utterly fantastic Sofra.

After lunch, we passed a couple pushing an infant in a baby carriage and a few lone walkers. For the most part, sightings of other humans were rare. We peered into mausoleums and were pleasantly surprised to see some lovely tiled floors. We didn’t see any snakes.

Life—and death—was good.

Perhaps the swarms of toads we encountered should’ve been a sign that menace was lurking in our future. As we made our way around a lake, Georgia and I realized that the ground was undulating beneath us. We leapt onto a nearby marble bench and looked down, aghast, at the writhing landscape.

So THAT’s what those “toad crossing—road closures” signs meant.

According to Mt. Auburn Cemetery’s website:

American Toads lay their fertilized eggs in water, where they hatch into tadpoles and metamorphose into toadlets before developing into adult toads. These amphibians need a safe, undisturbed body of water to lay their eggs in. In the late spring thousands of metamorphized toadlets emerge from Halcyon Lake and begin their journey fanning out into the landscape to grow and spend their adult lives, reaching breeding age in two to three years.

“Ugh, how many of those things do you think we stepped on?” Georgia groaned.

An investigation of the bottoms of our shoes revealed incriminating dark splotches. In our defense, we were more saddened by the deaths of the toads than horrified by the evidence on our soles. As soon as we identified a non-moving pathway, we hopped off the bench and hoofed it away from the decidedly non-halcyonic lake.

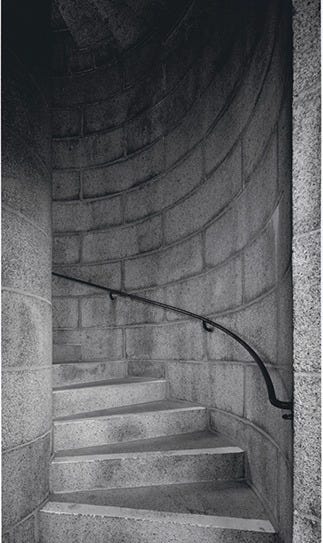

I’d mentioned to Georgia the existence of a tower that provided a nice, 360-degree view of the Boston area. We decided to climb it, then call it a day. Washington Tower is a 62’ foot tall granite tower designed in the English Norman (i.e., fortressy castle) style that stands atop a 125’ hill. In addition to honoring our nation’s first president, the purpose of Washington Tower is to be an easily identifiable location within the cemetery that also gives visitors a panoramic view of the landscape.

What architects Jacob Bigelow and Gridley J. F. Bryant (you may have read about him last year in Liberty at Last: An Ironic History of the Charles Street Jail and Its Architect) probably didn’t anticipate was that visitors might become trapped with an unsavory character at the top of the tower.

As Georgia and I climbed the dark, curving staircase, we heard what sounded like a death metal concert above us. When we arrived at the top, the music abruptly stopped. In front of us stood Goth Man Caricature, his face the whitest of white, his hair a shoulder-length nest of greasy black waves. His tall, moody figure was attired completely in—wait for it—black, from the top of his hoodie to the tip of his steel-toed combat boots. He picked up his now blessedly silent boom box and turned toward the stairs from which we had just emerged.

“You left your candy bar,” Georgia pointed out helpfully to Goth Man.

He lifted his deathly white visage from the depths of his black hoodie.

“That candy bar is not mine. I do not eat sweets,” he informed us before retreating back into his lair of a hood and starting down the stairs.

You probably suck the blood out of people’s necks to support your vampire lifestyle, I thought.

Georgia and I looked at each other, relieved to be rid of this menacing? pathetic? both of the above? figure.

“Well, then, look at this view,” I said with false enthusiasm, taking a few cursory steps around the top of the tower.

I stopped at the top of the steps and, feeling that something was not quite right, looked down. A figure in black was visible around the first curve of the stairwell, his hooded head turned slightly toward me. He didn’t move.

I scampered over to Georgia, pointed at the stairs, and stage-whispered, “He’s still there, standing on the stairs.”

Her eyes widened and, as we discovered later, we were both thinking the same thing. The railing wasn’t that high and we were 62’ feet from the ground. Did Goth Man mean to push us over? Was he on drugs and therefore easily able to take on both of us in his adrenalin-fueled frenzy?

As we were contemplating our next move, a pickup truck with the blessed words “Mount Auburn Facilities” on its side pulled up at the base of the tower. Our hero! We were saved! During the next few minutes, our hopes dwindled as no one emerged from the truck and it drove away. It was like that moment in a horror movie when rescue seems assured—until it isn’t. When Glenn Close is dead in that bathtub—until she isn’t.

During this time, no figure in black had emerged from the bottom of the stairs. About 1/3 of the way from the top of the tower there’s another “outside gallery with battlement,” as Mt. Auburn’s website describes it. Was Goth Man lurking there, ready to do battle with us?

“Christina, I really think we should call 911 or the visitors center,” Georgia said.

“I don’t know, I would feel ridiculous,” I replied.

“Better ridiculous than dead,” she said.

Point taken.

I removed my phone from my pocket, then gave one last look over the railing. The baby-carriage-pushing couple we’d passed was just arriving at the base of the tower. My first thought was, “How on earth did they get that baby carriage up all the stairs? That’s hardcore,” followed immediately by “Help has arrived.”

“Hellloooo!” I shouted from atop the tower, waving my arms. “Hellooo down there!”

The father looked around, puzzled, then up.

“Hi?” he called gamely.

“WE HAVE A SITUATION UP HERE,” I yelled, and it truly was yelling in all caps. “Can you stay there for 2 minutes until we get down there? And if we aren’t down in 3 minutes, can you call the police?”

“Okay, sure,” he answered, to his eternal credit.

“Let’s go, let’s go,” I urged Georgia, who was looking at me skeptically.

“He hasn’t come out of the tower, what if he’s on the stairs waiting for us with a weapon?”

“I have this,” I answered, drawing my umbrella from the loop around my wrist and simulating a sword. Since I was brandishing the flimsiest CVS umbrella imaginable, Georgia looked even more skeptical. When I’d purchased that umbrella, it made sense: I had invested several years before in an adorable “Raining Cats and Dogs” umbrella, then left it on a commuter rail train. Now, I only buy the least expensive, most boring umbrellas I can find so that I don’t become too attached or go bankrupt before losing them.

“You go first, and I’ll cover for both of us,” I said. I thought I was being gallant by letting my guest go first but, in retrospect, Georgia would’ve been the one stabbed or otherwise harmed first. She, in turn, had visions of me lunging at Goth Man with my flimsy umbrella, missing, and tumbling down the stairs.

“What if he heard you? I’m sure he heard you when you yelled.” I’m sure she was right: I’m pretty sure people in New Hampshire heard me.

“Then he’ll know we’re on to him and that help is on the way,” I replied.

We slunk down the stairs and there he was: half in and half out of the doorway at the lower battlement. I don’t even remember whether he was looking at us, I just waved Georgia past like I was guiding a plane toward its airport gate. My hand tightened around my umbrella handle as I spun around on the stairs so that I could keep an eye on Goth Man as I descended backwards. In retrospect, that was a really bad idea since I’m one of the clumsiest people on the planet and broke my arm in 4th grade while running backwards.

We emerged, alive and unharmed, to the sight of the baby-carriage-pushing couple, who had remained as promised at the bottom of the tower.

“Thank you, thank you so much!” we said in unison.

They smiled, waved, and proceeded on their walk, pushing the baby carriage as though no SITUATION had ever occurred. It HAD occurred, right?

Georgia and I turned and looked up at both battlements but we saw nothing: no black hoodie, no white face. We did, however, hear the insistent beat of death metal from somewhere up above us.

I felt ridiculous, but alive.

Such a fun read! Now I want to go there!!

Creepy but well done!