Earlier this month, a Clink Dinner Series invitation appeared in my email. I clicked, I perused, I thought the meal looked promising, primarily for its lack of “corned beef” or “cabbage.”

After confirming my husband’s interest in partaking, my thoughts turned to the several levels of irony baked into this seemingly innocent summons to dine.

Ironies for which the above invitation has been found guilty:

High-end restaurant called Clink is housed in a former Boston jail;

The Liberty, “a Luxury Collection Hotel, Boston,” also now operates within the renovated walls of what was once the Suffolk County, a.k.a., Charles Street, Jail;

Executive chef at high-end restaurant housed in former jail is jazzed about creating a meal inspired by the food and drink of Boston’s once-despised Irish immigrants;

A disproportionate number of Irish immigrants likely were held at Charles Street Jail and other Boston lockups, a supposition borne out by subsequent research.

Subsequent research that, as you will see, served up a generous helping of tasty, and often ironic, historic morsels.

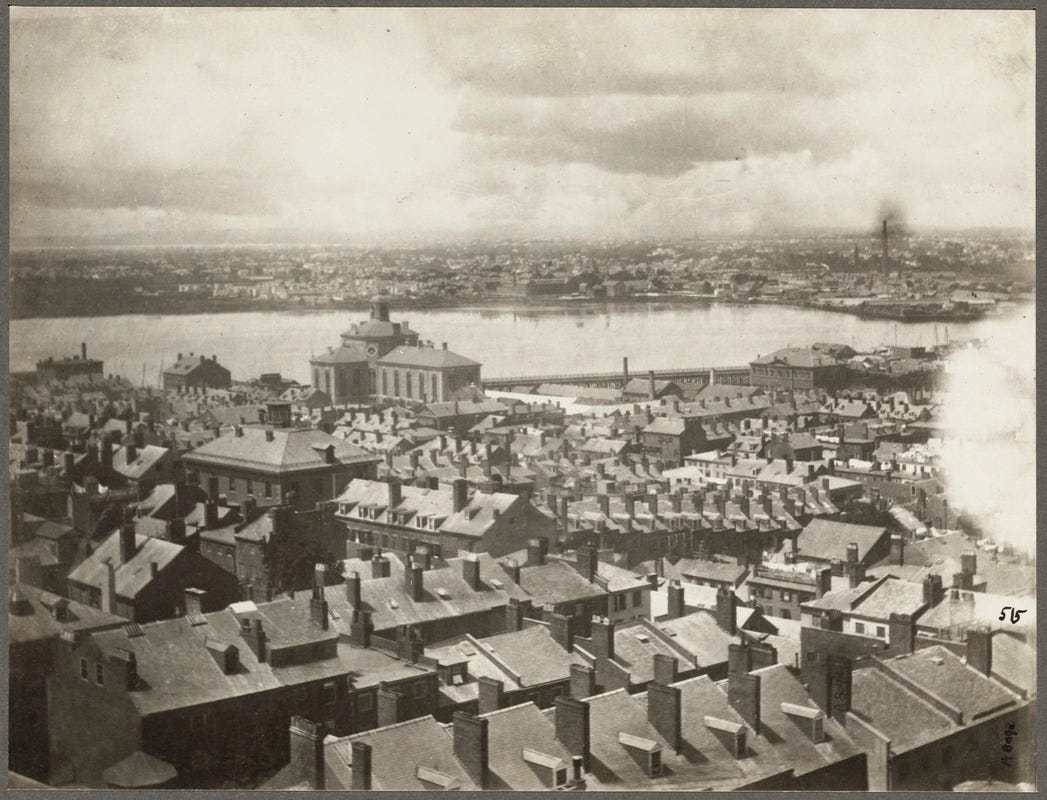

In 1822, Boston’s Leverett Street Jail opened its doors to short-term offenders and those awaiting trial. The place was a disaster from the get-go. Plagued by overcrowding and a litany of infrastructure issues, the grim granite building also was contentious for housing both men and women, for holding petty criminals—drunkards, dissenters—with murderers.

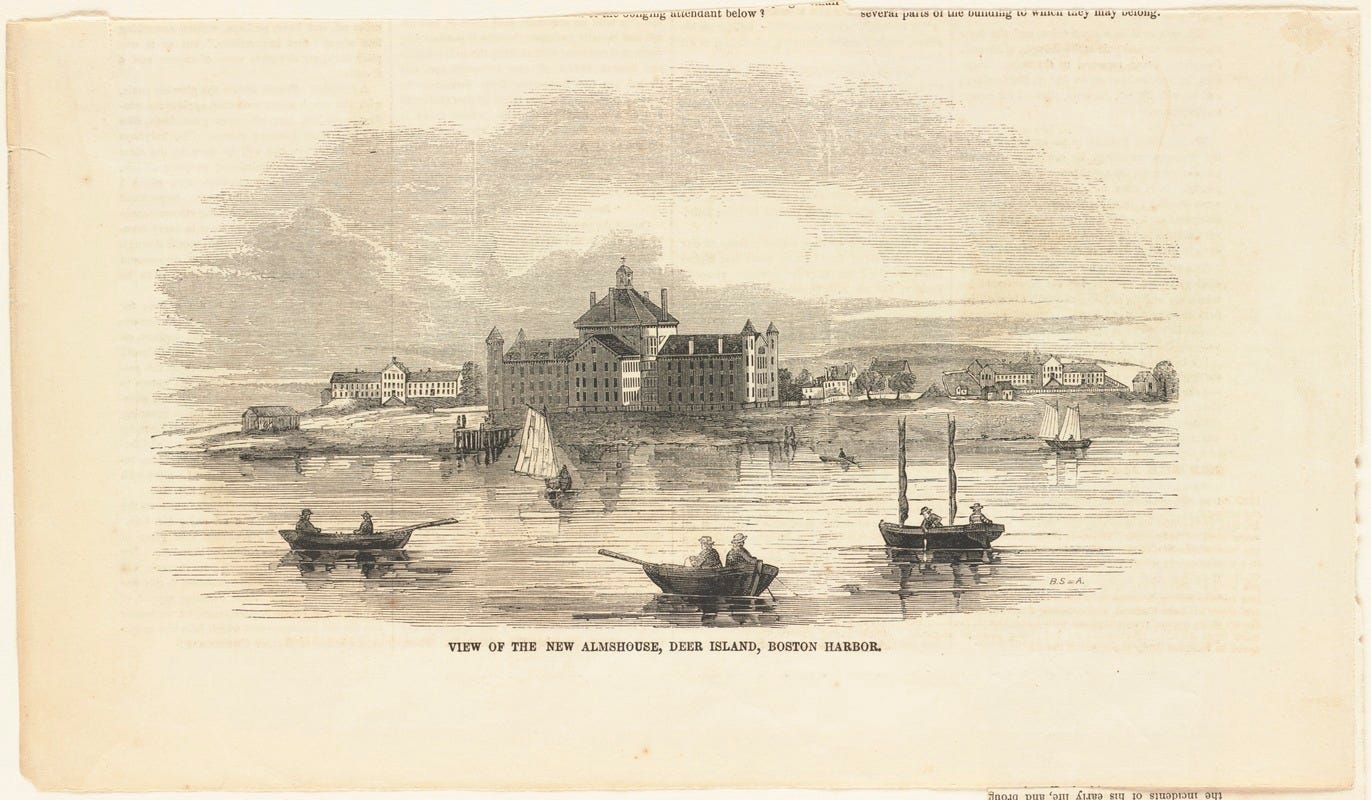

In 1845, architect Gridley J.F. Bryant and theologian/prisoner reformer Louis Dwight designed a kinder, gentler facility. Their plans were derailed by NIMBYs in South Boston, site of the proposed new jail.

Bryant and Dwight went back to their drawing board and devised an even more reform-minded building for a to-be-landfilled site on the Charles River. No pre-existing land with pre-existing houses, no NIMBYs to pooh-pooh the project.

The Charles Street Jail finally opened for business on November 21, 1851. As Roger Reed wrote in Building Victorian Boston: The Architecture of Gridley J.F. Bryant: “The city of Boston had a prison that reflected the most progressive thinking in penal reform, as well as a major architectural landmark that bolstered its popular self-image as a modern city.”

While Gridley J.F. Bryant’s name is little known today, he was the major practitioner of the Boston Granite style. You may think of Boston as a quaint, red-bricked city, but the bulk of its 19th-century buildings were crafted from the granite that is plentiful in the area. Bryant was the city’s most prolific and wealthiest architect from the early 1850s until 1872, when nearly all of the 150+ structures he designed burned to the ground in the Great Boston Fire.

In another sad irony, Gridley died penniless, he and his wife having lived beyond their substantial means. But he didn’t pass in just any poor house: from 1893 until his death in 1899, Gridley lived at Boston’s Old Men’s Home, a building he’d designed in 1855 as the Lying-In Hospital for impoverished women.

One of Gridley Bryant’s buildings that survived and still stands is Boston’s Old City Hall. I’m going to let the pictures of Old City Hall, which Bryant co-architected with Arthur Gilman, and the Brutalist monstrosity that replaced it in 1969 speak (mostly) for themselves.

“Yes, Boston’s new City Hall is a hideous building that has been justly proclaimed Boston’s/New England’s/the universe’s Ugliest Structure of All Time,” you may be saying. “And, while I’m curious about that statue, what happened to the Charles Street Jail?”

I’m glad you mentioned the statue. Richard Saltonstall Greenough, possessor of one of the most Boston Brahmin names ever, sculpted that figure of Benjamin Franklin, who was Boston-born and bred until he decamped for Philadelphia at age 17. Ben’s likeness stands on the site of America’s first public school.

As for the Charles Street Jail: although built as an Auburn Prison System exemplar, it devolved into just another overcrowded, underfunded urban jail. In the 1920s, Sheriff John Keliher upgraded the deplorable conditions, and the city did some intensive media blitzes touting the facility’s re-vamped amazingness.

While touring the Charles Street Jail in 1926, Red-Sox-player-turned-Yankee Babe Ruth prophetically proclaimed that, “It isn’t like a jail—it’s like a hotel.”

During the Depression, Charles Street Jail slid into decline once again and never recovered. By the early 1970s, inmates were filing lawsuits over being held in Constitutionally prohibited “cruel and unusual” conditions and rioting when they discovered bugs floating in their pea soup. On the other side of the iron bars, protestors were demonstrating and presumably stopping at the legendary Buzzy’s Roast Beef for sustenance.

In 1973, Judge W. Arthur Garrity, of Boston school desegregation/busing fame/infamy, spent the night in Charles Street Jail as part of his research into the inmates’ lawsuit. Not surprisingly, he ruled in favor of the plaintiffs. The jail was ordered to close for good in 1976, though it continued to house what it’s safe to assume were highly disgruntled inmates until 1990.

And then? In the mid-2000s, the Charles Street Jail was transformed into a luxury hotel called the Liberty. Cells were gutted, 150 years of what must have been truly disgusting paint was scraped, and any remaining evil juju was cleansed by Hindu monks. The Liberty now boasts 18 (voluntary) guest rooms in the renovated jail area, 280 rooms in a newly built tower, and dining and drinking options called Clink, Scampo (Italian for “escape”), and Alibi.

Such monikers for eating and drinking establishments located within a former jail turned Liberty Hotel will strike some people as offensive. A friend who worked at a law firm in the late 2000s told me that her company refused to have its annual holiday party at the Liberty for fear of offending its clients. My friend was offended at not being able to celebrate in one of the city’s buzziest new venues, so we’re going to pay a visit to the Alibi next month.

On the other hand, the names are pretty damn clever.

And wouldn’t people who were chucked into the slammer (I sincerely hope that Alibi has a drink called The Slammer—if not, you’re welcome, Alibi) in 1851-52 as “common drunkards,” or for “removing house offal,” for “malicious mischief” or numerous other quaintly named offenses, appreciate the irony themselves?

Wouldn’t they shake their heads at what the place has become and think, “Damn! If only I could walk through these doors, under my own steam, 172 years from now?”

Given how loathed they were during the 1800s (“Idle, thriftless, poor, intemperate, and barbarian,” thundered Reverend Theodore Parker. Turning Boston into a “moral cesspool,” opined Boston Mayor John Prescot Bigelow.), the Irish among them would definitely appreciate the irony of an upscale, four-course meal inspired by their homeland served in the clink in which they were once confined.

I think they’d enjoy that irony even more than I do.

Sources:

McMaster, Joseph. Images of America: Charles Street Jail. Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, SC. 2015.

Reed, Roger. Building Victorian Boston: The Architecture of Gridley J. F. Bryant. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, MA. 2007.

O’Connor, Thomas H. The Boston Irish: A Political History. Northeastern University Press, Boston, MA. 1995.

Handlin, Oscar. Boston’s Immigrants, 1790-1865. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. 1941.

https://cityofboston.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_52d6856b-c5e8-432d-88f0-4f21923534e2/

https://info.aia.org/aiarchitect/thisweek07/1012/1012p_jail.htm

https://thewestendmuseum.org/news/crime-scene-the-west-ends-three-jails/

https://beatleyweb.simmons.edu/collectionguides/CharitiesCollection/CC001.html

https://memory.loc.gov/master/pnp/habshaer/ma/ma1400/ma1444/data/ma1444data.pdf

History tour of Liberty Hotel with Concierge Mark at 2:00 p.m., March 13, 2024.

“Fine writing space” - you hooked me! Now I need to visit this place!

Fun read! Now I need to come visit so we can drink at the Alibi.