No, you don’t.

Not the entire thing, not unless you have several eight-hour days to dedicate to the task or endless stores of mental and physical stamina.

I speak from experience. One day last week, I attempted to walk The Freedom Trail’s entire 2.5 miles of red-painted/bricked walkway, stopping only to get a closer look at sites of interest or to use Ye Olde Restroom.

After four hours, I arrived at Faneuil Hall on sore feet and an empty stomach. I’d only made it to stop 14 of 23 on the National Park Service’s Self-Guided Freedom Trail audio tour; however, visiting sites 15-23 was out of the question. I lacked the energy to do more than skim the wealth of historical information at Faneuil Hall, then drag myself to the Boston Public Market, where I devoured a banh mi at Bon Me.

The Freedom Trail had defeated the no-longer-bon me.

It’s not like I’m a stranger to the Freedom Trail. During the 30+ years that I’ve visited or lived in the Boston area, I’ve taken ranger-guided tours covering various chunks of the trail. I drop by the Granary Burying Ground, the Massachusetts State House, and other sites along the Freedom Trail a few times a year. Heck, when I lived in the North End, I’d walk several times daily past the statue of the man, the myth, the legend: Paul Revere, swaggering on horseback in his eponymous plaza, a site that Freedom Trailers pass en route to stop 16, the Old North Church.

As I sat slumped in my Orange Line seat on the way home, I realized that the Freedom Trail hadn’t exactly defeated me, but that my attempt to walk it at warp speed had been misguided. My intentions were well-guided: I’d wanted to get a sense of what visitors to Boston’s Freedom Trail experience in trying to absorb its history, which frankly can be overwhelming even in small doses.

As the T stuttered along at about the pace I could’ve walked—we’re having some issues here in Boston with our poorly maintained, first-in-the-nation subway system—I got to thinking: when did the Freedom Trail become a thing? And who decided which of Boston’s gazillions of historic sites would be included? A Harvard-trained historian? Some National Park Service specialists?

No! A Boston newspaper reporter birthed the Freedom Trail.

On March 8, 1951, self-proclaimed Swamp Yankee (i.e., a rural New Englander with a penchant for living in the past) Bill Scofield wrote in his Herald Traveler column:

“I hope Mayor John B. Hynes and Harry J. Blake are listening today because I'm about to come up with an idea that would pay back diamonds for dimes in terms of good public relations. . . All I'm suggesting is that we mark out a 'Puritan Path' or 'Liberty Loop' or 'Freedom's Way' or whatever you want to call it, so [visitors and locals will] know where to start and what course to follow. ... [Y]ou could do the trick on a budget of just a few dollars and a bucket of paint.”

Apparently, the mayor of Boston and the president of the Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce were listening, or they got tired of being hounded in Scofield’s columns, because, by June, the sites that he proposed were identified with wooden markers.

Wow, a governmental body signed, sealed, funded, and delivered a project in a mere three months? If you ask me, that’s the most impressive part of this story.

During the 1950s, metal markers depicting Paul Revere riding hell for leather on horseback replaced wooden guideposts, brochures were printed, and tourists flocked to the Freedom Trail. A local businessman/philanthropist helped forge a coalition of private and public sector groups that own and operate featured sites, while the Boston Advertising Club and Chamber of Commerce sponsored and managed the Freedom Trail during its formative years.

As columnist Scofield predicted, tourists’ “diamonds”—or at least their open wallets—were paying back handsomely the “dimes” spent on red paint, a few signs, and some marketing materials.

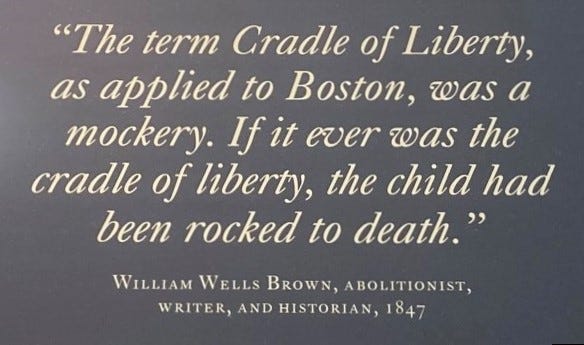

You may have noticed that “good historical practices” are missing from the Freedom Trail equation.

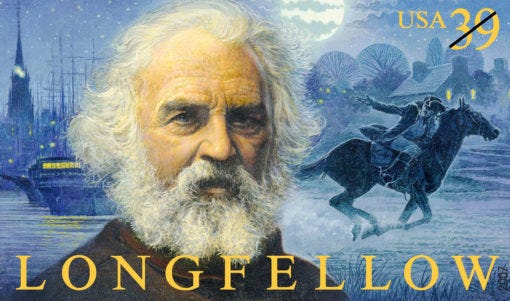

In his recent book Lost on The Freedom Trail: The National Park Service and Urban Renewal in Postwar Boston, historian Seth Bruggeman contends that the Freedom Trail “is a walking tour of (Henry Wadsworth) Longfellow’s historical imagination,” a trek through the poet’s romanticized version of the American Revolution as rendered in The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere.

Huh. Interesting. But, yeah, I can see that. The 2007 stamp pictured below has the “cozy history” aura that I associate with the Freedom Trail.

Given that the Boston National Historic Park was built around and now incorporates the Freedom Trail, this lack of historical rigor is a problem. Kind of an important one, if you’re touting a world-famous attraction that draws 4,000,000+ tourists annually to Boston under the guise of history.

Fortunately, the National Park Service has significantly ramped up its efforts in recent years to present a more comprehensive story of freedom as it was won, denied, or stolen from all of Boston’s citizens. The NPS has done this by incorporating more diverse stories into existing Freedom Trail sites and by mapping out such routes as The Black Heritage Trail and the Women of Beacon Hill Tour.

Then there’s the Freedom Trail Foundation, which is not part of the National Park Service. In fairness to this organization, it doesn’t actually promote "good” or “rigorous” history. The Freedom Trail Foundation’s web site features photos of men in breeches and tricorn hats and promises “a signature tourist experience.” Its brochure calls the Freedom Trail “Boston’s “indoor/outdoor history experience.”

“History experience?” Is the Freedom Trail Boston’s freaking Disneyworld? “History experience” summons an image of cartoonish Sam Adams and Paul Revere linking elbows and jigging around a tavern with tankards in hand, sloshing beer onto tourists in the poncho section (note: I made this Blue Man Group reference under the mistaken belief that BMG originated in Boston. Turns out that’s NYC’s cross to bear.)

If it sounds like I have it in for the Freedom Trail, I don’t.

The red brick/painted walkways, the sites, the mythology: it’s all become an integral part of "the Boston experience.”

The Freedom Trail has knocked it out of the ballpark—Fenway Park, of course—in bringing jobs and tourist revenue to Boston.

Its development saved some important historical buildings that would have been demolished during Boston’s period of frenetic, mid-20th century urban renewal.

The Freedom Trail has introduced millions of people to many of Boston’s Revolutionary War sites and events, albeit through a narrow historical lens that’s a bit scratchy.

I know from experience that dipping into the Freedom Trail a few sites at a time is educational and can be interesting, if not “hahaha,” Beauty-and-the-Beast-and-the-teapot-and-other-normally-inanimate-objects-dancing-about-the-castle entertaining.

My point is that the Freedom Trail is one (famous) itinerary of Revolutionary War-era sites located in a tourist-friendly area of downtown Boston. A couple of white men—a newspaper reporter and his pal who gave tours at the Old North Church—chose what to include and what to exclude.

Before setting out on the red brick road, it’s important to realize the origins of the Freedom Trail, and what you might anticipate vs. what you’ll actually find.

What do you hope to experience by strolling through Boston and viewing some of its historic sites? Perhaps, like me, what you’re seeking is an enlightening and enjoyable walk around the city, one that encourages ruminations about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, but that doesn’t feel like you’re cramming for The Biggest History Exam Ever.

In the next installment of Christina’s Travels, I’ll share my favorite historic sites both on and adjacent to the Freedom Trail.

Do you have Freedom Trail favorites? Share them in the comments section!

Resources referenced:

https://www.nps.gov/bost/index.htm

https://www.nps.gov/bost/learn/historyculture/upload/NPS_Boston-NHP-Administrative-History.pdf

https://www.paulreverehouse.org/longfellows-poem/https://www.thefreedomtrail.org/

https://www.thefreedomtrail.org/sites/default/files/content/PDFs/inventing_the_freedom_trail.pdf

https://www.thefreedomtrail.org/sites/default/files/content/Visit/Resources/freedom_trail_official_online_brochure_2020.pdfhttps://www.nps.gov/bost/index.htm

Boston A-Z, by Thomas O’Connor, published by Harvard University Press, 2001

Lost on the Freedom Trail: The National Park Service and Urban Renewal in Postwar Boston, by Seth C. Bruggeman, published by University of Massachusetts Press, 2022

http://www.hubhistory.com/episodes/lost-on-the-freedom-trail-the-national-park-service-and-urban-renewal-in-postwar-boston-episode-251/

digitalcommonwealth.org

Great post! I learned a lot! Didn't know who came up with the bucket of paint. Also, for folks who are interested, here is the link to the Black Heritage Trail tour:

https://www.nps.gov/boaf/virtual-black-heritage-trail-tour.htm

Well done! We have done the Freedom Trail and the Underground Railroad trail and now when next we visit you must take is on the Women’s trail. I like the cemetery because I perhaps morbidly like to look at the people and dates to try and figure out what led to their demise.