If our nation’s 8th president is so forgettable, then why, you may ask, did I bother touring his home?

One of the many things I’ve learned from visiting 20 presidential sites is that there’s zero correlation between a commander-in-chief’s favorability rating, personality, or politics and the enjoyability factor of visiting that person’s home or library. From observing how curators twist themselves into knots trying to justify their subjects’ ill-advised foreign policy decisions to wondering how painful it was for that guy in front of me at Monticello to get his “Live Free or Die” neck tattoo, each trip has been educational and entertaining on multiple levels.

While Martin Van Buren doesn’t appear on either C-SPAN’s or US News & World Report’s list of Top 10 Worst Presidents, I think it’s just because they forgot his existence. Okay, that was unkind. Poor Martin gets the history shaft primarily because, several days after he took office, the US entered its first major economic depression. Set in motion by Andrew Jackson’s breakup of the Second National Bank, the Panic of 1837 lasted throughout Van Buren’s single term in office. Getting stuck with the sins of your predecessor sucks, but that’s how democracies roll.

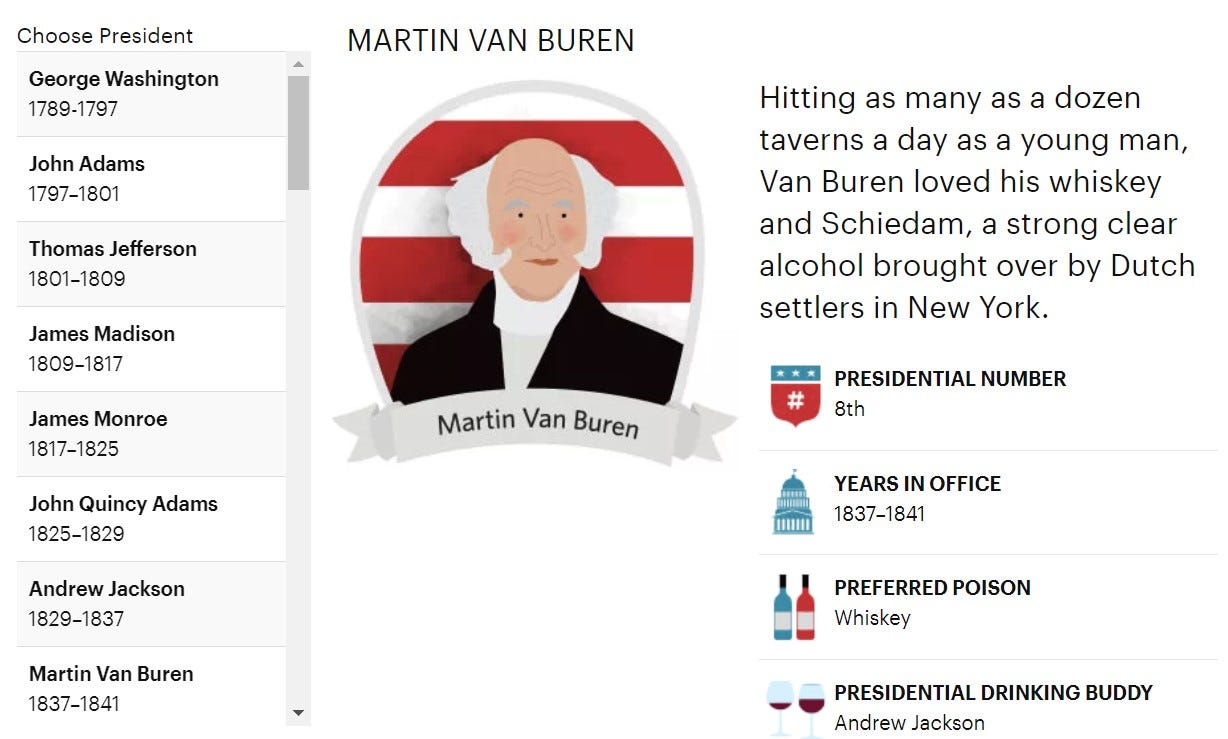

Martin Van Buren was born in 1782 in Kinderhook, NY, a small town about 1/2 hour south of Albany. He was raised in a tavern, which appears to have whetted his lifelong appetite for spirits (those found in a glass, not in a seance parlor).

Van Buren became a lawyer at 20. As he climbed nimbly up the political ladder, he was dubbed “The Little Magician” by those who respected his political craftiness. Those who were less admiring of this skill referred to him as “The Red Fox of Kinderhook.”

Following his presidential re-election defeat in 1840, “Old Kinderhook” returned to his hometown to live at Lindenwald, a house on 220+ acres of farmland that he’d recently purchased. “The Dandy”—our man Martin had a taste for the finer things in life—devoted much of his money and other people’s efforts into upgrading Lindenwald, where he lived as a gentleman farmer until his death in 1862.

If you’re chomping at the bit to learn more about the life and times of Martin Van Buren, I direct you to the podcast [Abridged] Presidential Histories with Kenny Ryan, Episode 8 and/or this article.

I visited the Martin Van Buren National Historic Site one sunny July morning in the company of Ranger Zack and a family from Indiana. Ranger Zack, who hails from Atlanta, was welcoming and chatty from the get-go. I wasn’t picking up similarly friendly vibes from the family of three: no eye contact (I sort of tried), no “hello”s, not even any comments about the splendid weather we were having, so I turned my attention to the guy repairing Lindenwald’s roof and hoped that the cables attaching him to the lift truck held.

Inside, The Dandy’s elegant yet inviting home was well-appointed with fine furniture, expensive wallpaper, and, most importantly, one of the earliest examples of indoor plumbing in a private residence.

Mind you, someone—and I don’t mean Van Buren or any of his family members—had to pump water from a well in the basement up to the flushing toilets, which those same someones were not permitted to use. I forget how much the Irish maids serving the Van Buren household were paid—sorry, Ranger Zack—but the term “working for slave wages” came to mind.

About halfway through the tour, Ranger Zack told us that Kentucky Senator Henry Clay was a recurring guest at Lindenwald. On one of these visits, his manservant took the liberty of liberating himself.

“You mean he was a slave who ran away?” I clarified.

Ranger Zack confirmed, and I asked whether this defection had occurred before or after the Compromise of 1850, “with the Fugitive Slave Law and all.” Turns out Clay and Van Buren were discussing this very matter when the attentive manservant decided it was time for a one-way trip to Canada. Once enacted, the Fugitive Slave Law allowed slave owners to search for and seize their human property in states where slavery was outlawed. It did a bang-up job of further alienating northerners and southerners while kicking the Civil War can down the street another 11 years.

Shortly after I’d introduced the Fugitive Slave Law into the conversation—rather smoothly, I thought—Ranger Zack informed us that, at 5’6,” Martin Van Buren was the second shortest commander-in-chief.

“Does anyone know who the shortest president was?” he inquired.

“James Madison, five feet, four inches,” the Indiana matriarch promptly answered.

Damn! I was impressed. Turns out she’s a teacher with a treasure trove of presidential knowledge. I mentally chastised myself for writing her family off as bumpkin tourists, then realized they may well have seen my Mini Cooper with Massachusetts plates in the parking lot and written me off as a snooty libtard. Which could’ve been why they avoided talking to me almost as studiously as I’d avoided engaging with them.

Lessons having been learned and better tour group karma having been established via respect for one another’s historical knowledge, we chatted and “you first”ed each other through doorways during the rest of the house tour.

Remember way back in the second paragraph, when I said that every presidential site has been well worth the visit? My major Martin Van Buren National Historic Site moment came when I stopped in the doorway of Abraham and Angelica Singletary Van Buren’s bedroom.

I doubt that many people get gobsmacked when they enter the room of Martin Van Buren’s oldest son and daughter-in-law. And, although Angelica appears to have been a stunning-looking woman, her beauty isn’t what drew me deeper into the room.

Seeing Angelica’s portrait whisked me back to the 1970s, when I was a frequent and enthusiastic visitor to the First Ladies Hall at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of History and Technology, as it was called at the time. I loved walking among the low-lit glass cases of mannequins attired in fancy, old-fashioned dresses worn by the presidents’ wives (or those who, like Angelica, served as hostess for a president whose wife had died, or who was a bachelor). Staring into those displays, with their period-appropriate furnishings and architectural features, I felt both deeply connected to history and fully immersed in the moment.

The only thing that got me to move along was the prospect of visiting the gift shop.

Perhaps because there was no Presidents Hall at the Smithsonian, I was under the impression that the first ladies were the presidents (an impression that was not mistaken in some cases: I’m looking at YOU, Edith Wilson). Or maybe it’s because it was the 1970s and my mother had one of those “A Woman Without a Man is Like a Fish Without a Bicycle” T-shirts and that Helen Reddy song “I Am Woman, Hear Me Roar” was all over the radio and I just figured women did everything important.

During my period of First Ladies Hall fandom, I wrote a story that I wish like hell I could locate about the mannequins hanging out at night, taking tea, and learning about one another’s lives and times. Here’s how a mashup of dialog written by younger me and current me might sound:

Mrs. Harding: “Warren G. and I purchased a new Victrola for the East Room. The sound is divine!”

Mrs. Nixon: “Oh, honey, recording technology has come such a long way since the 1920s. Can you please pass the sugar?”

Of all the first lady mannequins, Angelica Van Buren, with her ostrich-feathered hairpiece and hoopskirted blue velvet gown, was my favorite. As I discovered recently when reading through my well-worn copy of The First Ladies Hall guidebook published in 1973, each mannequin’s face was based on the same sculpture of Cordelia, daughter of Shakespeare’s King Lear.

Well, that solved a mystery that had been niggling at the back of my mind for 45+ years: why did all of the first ladies have such ethereally beautiful mannequin faces when a glance at their portraits or photographs showed that they were normal-looking women with odd hairdos?

Actually, I hadn’t thought about the First Ladies Hall for ages, not until I saw that portrait of Angelica Van Buren on the wall of her room at Lindenwald. Forgotten though it was, the First Ladies Hall has had a meaningful impact on my life, just as all of our presidents—even Martin Van Buren, largely consigned to oblivion—have impacted our country and its history. Recognizing the contributions of our presidents—positive, negative, or somewhere in between—and how their decisions affect our lives and our democracy now, seems like a darn good reason to take an hour or a day to visit their sites and remember them.

Are you jazzed up to visit some presidential homes, libraries, and tombs? Of course you are!

Sign me up, Sandy! I've never been to a Hoover site and it would be a lot of fun re-connecting with you and doing that hike!

Also I must get the drink book!