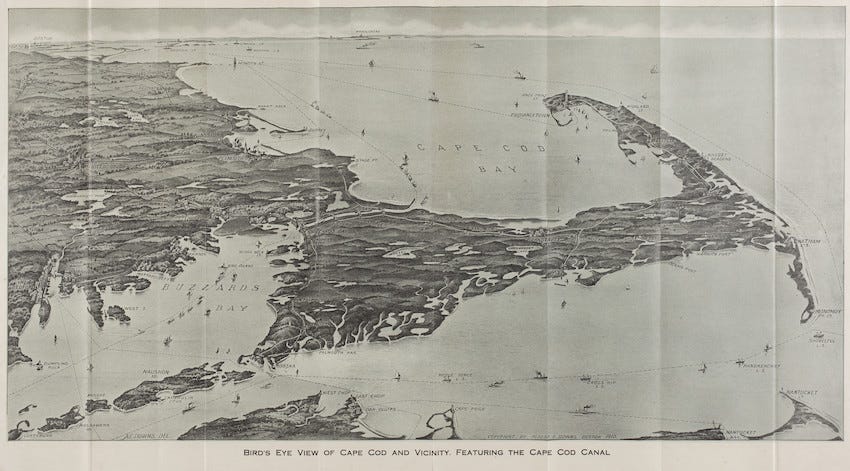

Before looking at Google Maps last week to see how long it would take me to drive from HOME to THE FISHERMAN’S DAUGHTER, CHATHAM MA, it hadn’t registered with me that Cape Cod is actually an island.

The Sagamore and Bourne bridges, either of which is required to reach Cape Cod by car, should’ve been tipoffs; however, I’d viewed them only as obstacles to be overcome in an attempt to make the Martha’s Vineyard ferry or dinner with my daughter on time.

In my defense, for tens of thousands of years, Cape Cod was an actual landmass extending into Buzzards Bay, Cape Cod Bay, and the Atlantic Ocean. For nearly as long—I exaggerate, but literally since they first laid eyes and feet on the cape in the early 1600s—European colonists had been itching to convert Cape Cod into “Island Cod.”

Why is Island Cod preferable to Cape Cod? Why did it take 300 years to detach the cape from the mainland? Most importantly, how does Man O’War, the greatest racehorse of all time, figure into this story?

Once upon a time, a river called the Manomet flowed into Buzzards Bay. A river named Scusset emptied into Cape Cod Bay. Located tantalizingly close to one another—about a mile in crow-flying distance—the two bodies of water never actually met.

This presented both economic and personal discomfort issues for the Pilgrims. They wanted to trade with the local Wampanoags and with the Dutch sailing north from New Amsterdam, a city that’s been known since September 8, 1664, as “New York.” Conducting such trade required the Pilgrims and subsequent colonists to sail up one river, then portage (a.k.a., “carry their canoes and the goods they were trading”) a few miles to reach the other river and finish their journey.

Taking the ocean route around Cape Cod—as more and more ships did over time and as trade increased—was dangerous. The ocean floor off the cape is riddled with shoals, and the currents are vicious. By the late 1800s, an average of one ship per week either was stranded or sank off the Cape Cod coast.

Mayflower passenger and Plymouth Colony military leader Myles Standish first suggested building a canal between Buzzards Bay and Cape Cod Bay to make trade more efficient and less dangerous. This was in the 1620s. If I were to list every person, government entity, and private concern that advocated for building a Cape Cod Canal, commissioned a study on the feasibility of and/or the best way to construct a canal, pledged funding for a canal, and even put spade to rocky dirt in an attempt to dig a canal between the 1620s and 1909, you would fall asleep within moments. Assuming you haven’t already done so.

Enter August Belmont, Jr.

Like his father, August Jr. was a New York financier who hobnobbed with the likes of J.P. Morgan and John D. Rockefeller. Also like his father, August Jr. was smitten with horse racing. You know how the Triple Crown consists of the Kentucky Derby, the Preakness Stakes, and the Belmont Stakes? August Jr. is THAT Belmont, the guy who bought the land for and built Belmont Park in the early 1900s.

In addition to spending money on horses and racetracks, August Jr. also invested in, and ran, transportation systems. In 1904, he financed the first New York City subway line. He led the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) for years. Flush with the success of his transportation ventures, August Jr. announced that he would be successful where so many before had tried and failed: he would build the Cape Cod Canal.

August Jr. obviously was a savvy businessman, or he wouldn’t have added to the fabulous wealth he inherited from his father. In this instance, though, hubris and sentimentality may have gotten the better of his business sense. His grandfather was Commodore Matthew Perry, who opened trade between Japan and the West after many centuries. Commodore Perry hailed from Bourne, MA, which, along with Sandwich, is one of two towns through which a proposed Cape Cod Canal would, and now does, run. Was this project meant to be a memorial to his grandfather, a true business investment, or both?

Whatever August Jr.’s motivations were, cutting a canal proved to be more difficult than either he or his chief engineer anticipated. Things started off promisingly enough on June 22, 1909, when August Jr. lifted his sterling silver Tiffany shovel and announced:

I promise in digging the first shovelful of dirt not to desert the task until the last shovelful has been dug.

To his credit, he did not desert the task, despite such obstacles as lack of proper dredging equipment, massive glacial boulders that had to be dynamited to pieces, bad weather (welcome to New England, August Jr.!), and the fact that the bodies of water being connected have drastically different tidal patterns.

For five years, Chief Engineer William Barclay Parsons applied his engineering prowess to the many problems that arose. Up to 1,000 immigrant and local laborers dredged, dug, dynamited, and otherwise labored to build the canal 24/7. August Belmont Jr. kept the money flowing. And then, as author J. North Conway writes:

On July 4, 1914. . .the last barrier between the east and west sides of the canal was broken and the once impossible dream of the Cape Cod Canal, after nearly 300 years of discussions, surveys and setbacks, became a reality.

The 8-mile-long canal was 100’ wide and only 15’ deep on July 29, 1914, the day it opened to traffic. Although the canal was supposed to be 25’ deep, August Jr. decided, as all Cape Cod businesses do, that he needed to take advantage of summer demand. Work on the canal could continue even while boat traffic navigated it, couldn’t it?

August Jr. must’ve realized that the Cape Cod Canal wasn’t going to be a financial success. During the dedication ceremony, he said:

Personally, should it (the new canal) serve no other purpose than the saving of thousands of lives from perishing off the Cape, I shall feel my own efforts are repaid.

That’s fortunate since his canal lost money from the get-go. Much of his vast personal fortune had been invested—or sacrificed, depending on how you view the situation—in building the Cape Cod Canal.

August Jr. decided to pay off his debts by selling some of his thoroughbreds. While he was in Europe fighting in World War I, he okayed the sale of his 1917 foals, including one that his wife had named for her 64-year-old husband warrior: My Man O’War.

My Man O’War, minus the “My,” went on to win 20 of the 21 races he ran for his new owner, Samuel Riddle.

But, hey, at least August Belmont Jr. had the Cape Cod Canal as a consolation prize. . .oops, no he didn’t. With German submarines lurking off the Massachusetts coast—one actually did strike a tugboat and sank the four barges it was towing—the U.S. government took over canal operations during the war.

In March of 1928, after a decade of negotiations, the government purchased the canal from Belmont’s Boston, New York, and Cape Cod Canal Company for $11.5 million. August Belmont Jr. had died in 1924. According to J. North Conway, “Belmont’s estate received approximately $4.5 million from the sale of the canal. Based on his overall investment, including interest, Belmont’s estate lost close to $5 million on the sale.”

And August Jr. lost the greatest racehorse of all time.

The Army Corps of Engineers spent the 1930s reconstructing the canal to widen, deepen, and lengthen it to accommodate two-way shipping and boating traffic. Now a vital part of the 3,000-mile intracoastal waterway, the Cape Cod Canal is 17.4 miles long, 480’ wide, and 32’ deep, making it the nation’s longest lock-free, sea-level canal. Seven miles of paved service roads on each side allow hikers and bikers to enjoy the comings and goings of boats and birds alike.

And, of course, there are those bridges crossing the canal to connect mainland Massachusetts to Island Cod. The Army Corps of Engineers rebuilt the three bridges—the Sagamore, the Bourne, and the lovely vertical lift railroad bridge—during the 1930s reconstruction.

Just yesterday, Massachusetts Governor Maura Healey announced that the Commonwealth has secured enough funding to replace the Sagamore Bridge, the one that serves as the main conduit from Boston to Cape Cod. The $2+billion project is expected to take 8-10 years to complete.

The thought of how much that construction project will snarl traffic is not what prompted me to purchase tickets for a 2-hour Cape Cod Canal Yacht Rock Cruise, which two friends and I may well be on as you are reading this. But drinking a Piña Colada while boating on the canal may be the perfect “Escape” for any of us who will have to deal with this impending traffic nightmare.

Resources

Conway, J. North. The Cape Cod Canal: Breaking Through the Bared and Bended Arm. The History Press, 2008

History Channel: Engineering the Cape Cod Canal/Modern Marvels (S11, E27)

Visit to Cape Cod Canal Visitors’ Center, July 11, 2024

US Army Corps of Engineers website and Cape Cod Canal brochure

https://www.americasbestracing.net/the-sport/2020-august-belmont-ii-the-man-who-bred-man-o-war

https://www.champsofthetrack.com/post/august-belmont-jr

Historic New England’s Nina Heald Webber Cape Cod Canal collection

Never heard this amazing backstory- where and how do you know to look for it? Always so interesting

I had no idea of any of this, being from the mountain West. Did not know Cape Cod is actually an island. Did not know how that came to be. Cool!