Imagine finding out that your best friend tortures small animals, or that 2+2=5, or that spring isn’t coming this year.

Or, to give these scenarios a historical slant: remember how you may have felt when you learned that George Washington owned slaves, or that the North and South gave different names to the same battles during the American Civil War, or that King Arthur is just a legend. (Sorry if that last bit came as a Santa-isn’t-real surprise to anyone.)

You’d be—perhaps were—shocked, confused, disappointed: namely, all the emotions I felt after researching the “real” story lurking beneath the historical novel that I was enjoying.

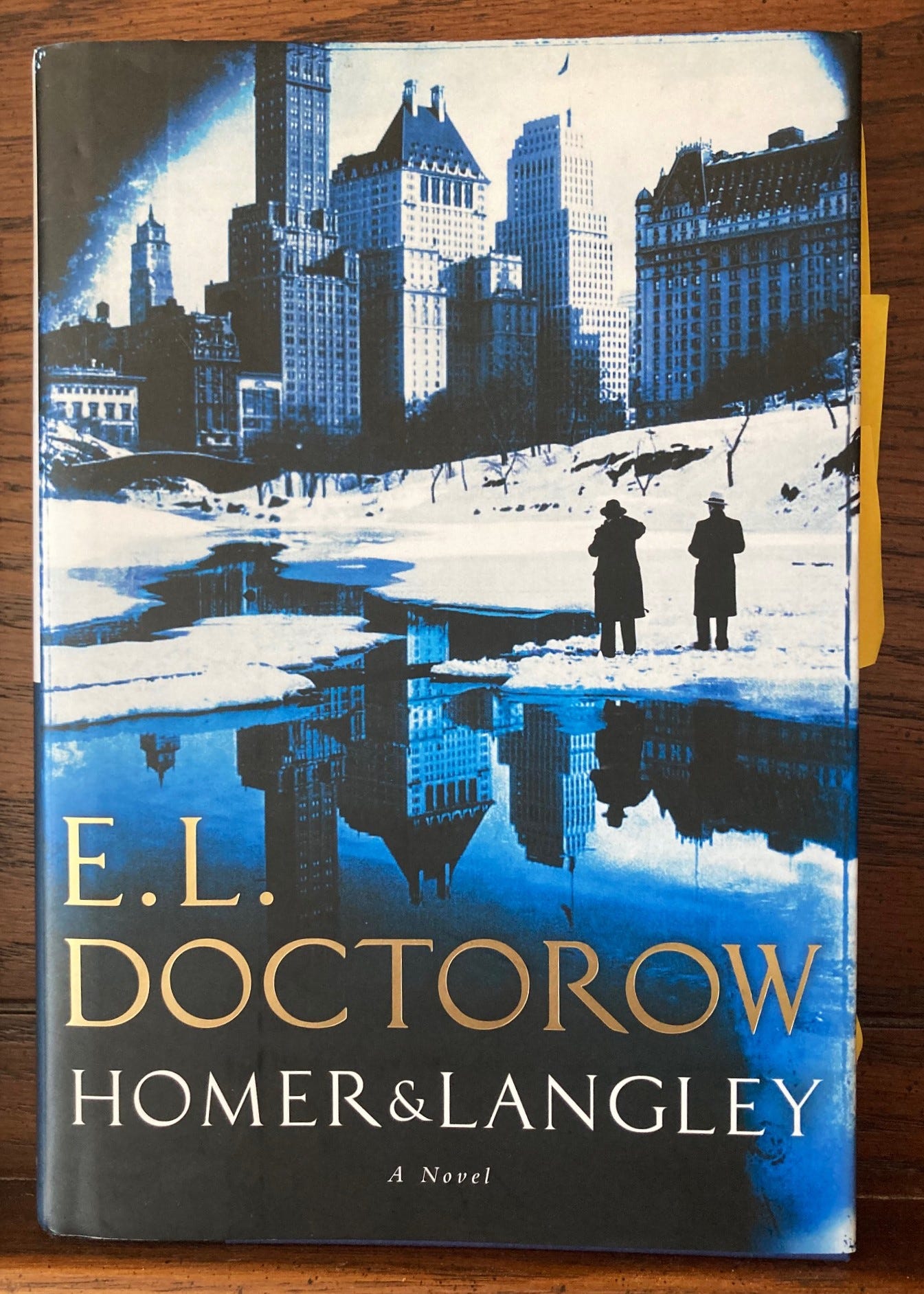

On a recent trip to New York, I picked up the novel Homer & Langley by the late, great E.L. Doctorow. I was drawn in by the cover, which captures how I feel when walking in Central Park on a winter day: chilly, blue, reflective, reveling in the lack of crowds.

I opened the book, scanned the dust jacket copy, and learned that Homer & Langley is about “brothers—the one blind and deeply intuitive, the other damaged into madness, or perhaps greatness, by mustard gas in the Great War. They live as recluses in their once grand Fifth Avenue mansion. . .”

Say no more, Random House marketing people. Dangle historic mansions, quirky characters, and World War I in front of me and I will pounce.

The next evening, I settled into an Amtrak cafe car—always snag a seat in the cafe car if you want to spread out and not have to worry about your stuff when you get up for snacks, beverages, or the bathroom—and fished Homer & Langley out of my bag to read on the trip back to Boston.

Doctorow’s opening words reeled me in:

I’m Homer, the blind brother. I didn’t lose my sight all at once, it was like the movies, a slow fade-out. When I was told what was happening I was interested to measure it, I was in my late teens then, keen on everything. What I did this particular winter was to stand back from the lake in Central Park where they did all their ice skating and see what I could see and couldn’t see as a day-by-day thing. The houses over to Central Park West went first, they got darker as if dissolving into the dark sky until I couldn’t make them out. . .

New Rochelle—Stamford—Bridgeport: the train must’ve stopped at every Northeast Regional station; however, I was so immersed in Homer/Doctorow’s world that only the conductor’s shout of “South Station, Boston, last and final stop” shook me out of it.

I’m pretty sure it was the redundancy of “last and final” that caught my attention more than the volume of the conductor’s pronouncement, but at least I was pulled out of Homer’s world and back into my own before an Amtrak conductor had to remove me from the train.

The next day, I plopped into my favorite living room chair with my cat Bandit and Homer & Langley. I’d read about half the novel, and was eager to lose myself once more in Doctorow’s chapter-free, flows-like-a-river storytelling about two men who clearly had issues but who were playing the game of life on their own terms, a book that is generally and incongruously uplifting.

I have no idea why I felt the urgent need to discover when the book came out but I went straight to the copyright page, a move that I now regret. Homer & Langley, I learned, was published in 2009, making it one of E.L. Doctorow’s last novels (he died in 2015). Above the copyright date, I read: “Homer & Langley is a work of fiction. Apart from the actual people, events, and locales that figure in the narrative, all names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.”

My eyes wandered down the page under the ISBN numbers to: “1. Collyer, Homer Lusk, 1881-1947—Fiction. 2. Collyer, Langley, 1885-1947—Fiction.”

Oh, these guys were real? I thought. Then, totally disregarding the numerous “fiction” disclaimers, I said out loud, “Langley is supposed to be the older one, not Homer. And did they both really die in 1947? What a weird coincidence.”

Apparently I vocalized too aggressively because Bandit gave me a baleful look, jumped off my lap, and stalked away.

And then (drumroll, please): shock, confusion, and disappointment engulfed me when I made the grave mistake of researching the reality of Homer and Langley Collyer.

Homer and Langley, dear Reader, were legendary hoarders. I’m not talking National-Geographics-stacked-on-the-back-staircase-level hoarders. What we’re dealing with here is a four-story Manhattan brownstone literally collapsing under the weight of thousands of books, tons of newspapers, 14 grand pianos, the carcass of a Model-T, baby carriages, mattresses, military uniforms, furniture, and so much more stacked floor to ceiling in every room, hallway, and closet.

We’re dealing with men who lived with their parents (gynecologist dad and singer mom who were also first cousins) until their mid-30s, when the parents separated. The boys continued living with mom in the brownstone, which they inherited when she died in 1929. After that, Homer was never again seen outside, and Langley only rarely, usually when going on midnight food-scavenging or yet-more-stuff-gathering runs. The Collyer brothers lived off the grid, refusing to pay their electric bills, disconnecting their phones, and ignoring insistent knocks on the front door.

Despite not wanting to attract attention, the Collyer brothers did just that because of their secretive natures and the growing piles of junk littering their yard and oozing from their house. To discourage intruders, Langley nailed shut the windows and doors, drew the blinds, and rigged up booby traps throughout the house to capture anyone crazy enough to venture within.

And Langley did catch someone: himself. Three weeks after neighbors reported a rotting smell emanating from the Collyer brothers’ mansion and police discovered Homer dead in a chair, they located Langley’s body across the room, crushed under one of his own traps.

Yes, it really did take three weeks to find a body located a mere 10 feet from the first body: that’s how crammed the house was.

As my husband would attest, my first few days post-Reality Reveal were rough. We’d be sitting at the dinner table and I would suddenly moan, “How?” And, sadly, I’d moaned enough at that point that my husband knew I was referring to the real lives of Homer and Langley, not to the story of Homer & Langley.

I finished the novel with a heavy heart and many Post-it notes alluding to what had “really” happened.

“No mention of changing Harlem neighborhood” I huffed in blue ink on one.

“Is the greater ‘truth’ more important?” I asked myself on another.

After several weeks of having the Collyer brothers—both Homer and Langley and Homer & Langley—swirl through my brain, I have concluded that yes, in the case of historical fiction, the greater truth IS more important than the literal facts.

In a happy coincidence, at the same time I was experiencing Collyer Brothers Reality Trauma, I also was reading The Deadline, Jill Lepore’s new book of essays, and came across one titled “Just the Facts, Ma’am.”

The first sentence is: “What makes a book a history?” and questions whether historical truth is truer than fictional truth. Lepore writes:

History matters, but the best novels boast a kind of truth that even the best history books can never claim. . . The difference between history and poetry, Aristotle argued, is that ‘the one tells what has happened, the other the kind of things that can happen.’

And there is so much truth, so much room for the kinds of things that can happen in Homer & Langley: what it means to make choices and not bemoan paths not taken, what it means to find refuge while the world outside is going mad, what it means to create beauty and solace where seemingly none exists.

What it means to bring two outsiders to life in an engaging and insightful narrative that seeks to explain how they turned out, and why they lived, as they did.

Excavating the real story of Homer and Langley Collyer’s lives destroyed my desire to re-read Homer & Langley. And that’s sad because, even as I was reading it—the first, pre-Reveal half, that is—I was looking forward to re-inhabiting the brothers’ world, messy as it was.

Lesson learned? I will judge historical fiction strictly on its own merits: style, characters, storytelling, world-building. I will not seek out the “real” story, only to have it emerge from a dark alley and punch me in the guts.

Homer and Langley’s brownstone was torn down in July, 1947, a few months after their bodies were discovered and removed, along with hundreds of tons of other decaying stuff. The site of the former Hoarder House is now a pocket park, a historical fact that is simpatico with my version of Homer & Langley’s truth.

References:

Doctorow, E.L. Homer & Langley. Random House, 2009.

Lepore, Jill. “Just the Facts, Ma’am” from The Deadline: Essays. Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2023.

Manshel, Alexander. Writing Backwards: Historical Fiction and the Reshaping of the American Canon. Columbia University Press, 2024.

The Bowery Boys podcast Episode #280: The House of Mystery: The Story of the Collyer Brothers.

So many YouTube videos and newspaper articles about the Collyer Brothers.

I love how you love to investigate things. I, in fact, don't believe that you will leave historical fiction alone! I think there will be more historical mysteries and blindsides revealed in the future! I enjoyed this piece. I've never read one of his books, so I enjoyed the literary tour.