We now return to the cunning little garden pathway next to The Mark Twain House Visitor Center from which my daughter and I have just emerged. If this makes absolutely no sense, I understand, and refer you to Part 1 of our early June day in Hartford, It’s Twain Time Again.

While waiting for our tour of the writer’s house, a friendly volunteer suggested that we visit the gardens next door at the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. The gray brick Victorian Gothic cottage where Stowe resided from 1873 until her death in 1896 is across the lawn from The Twain House, where the Clemens family lived from 1874-1891. Both were part of the Nook Farm neighborhood, a close-knit community of intellectuals, abolitionists, and local political aristocracy.

As Lucia and I meandered toward the Stowe Center, I asked, “Do you know who Harriet Beecher Stowe is?”

“Yes,” my 19-year-old daughter answered promptly. “She wrote that racist book about slaves.”

Huh, what?

It took me a few beats to process that we were both talking about the same Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. It’s one of the most famous and influential pieces of fiction in American history. If someone taking, say, an AP US Literature test was asked to describe Uncle Tom’s Cabin in five words, that person would be on solid ground answering “shows the evils of slavery.”

Not exactly a topic that a racist would tackle.

I took a really long sniff of the rose closest to my nose, stalling for time to formulate a coherent response from the jumble of thoughts swirling through my brain (“WT absolute F#*! are the schools teaching these days?” “My tax dollars!” “I sound like an old geezer.” “But, still, WTF?”).

I finally responded that, while Black people aren’t portrayed particularly well by today’s standards, Uncle Tom’s Cabin raised awareness of the daily plight of slaves and the systemic injustice of slavery. This, in turn, played a huge role in increasing support for the abolitionist movement in the north—before Stowe’s book came out, abolitionists were perceived by southerners and most northerners as fringe loony-toons—and, ultimately, support for the Civil War.

Lucia and I continued smelling roses, then we headed back across the lawn to our tour of the fabulously over-the-top Gilded Age gem that is The Mark Twain House.

For the past few weeks, though, I’ve been thinking quite a lot about the issues and questions raised by Lucia’s perception that Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a racist book.

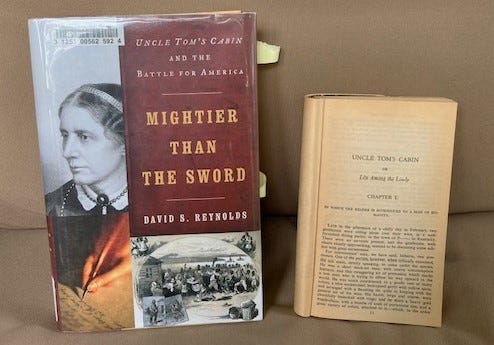

It’s easy to read Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 2023 and cringe. A lot. I know this because the first thing I did when we returned home from Hartford was pull out my paperback edition of the book, which I last read during my freshman year of college. Part of the cover crumbled in my fingers, a tactile reminder that my freshman year in college was a hell of a long time ago, and that Stowe wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin an even hell of a longer time ago: 172 years, to be precise.

After re-reading the first few chapters of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, I’d had more than enough. The “n” word is used liberally throughout, as it was in the 1850s by people of all races and classes. The religious imagery and moral proselytizing are saccharine, the language often melodramatic and dated, and sentences like “The boy commenced one of those wild, grotesque songs common among the Negroes” are jarring to a modern reader.

But, in 1851, when Uncle Tom’s Cabin was serialized in an abolitionist weekly called The National Era, and 1852, when it was published in book form, the style, themes, and language were completely relatable. What was radical was that Stowe portrayed slaves as human beings with thoughts, feelings, hopes, and goals—in short, she compared them to (gasp) white people.

Think of how hoop skirt/top hat raising this paragraph was to white readers in the decade before the Civil War, when Blacks were seen by most northern and southern whites as property or lesser humans:

“Sobs, heavy, hoarse, and loud, shook the chair, and great tears fell through his [Uncle Tom’s] fingers on the floor: just such tears, sir, as you dropped into the coffin where lay your first-born son; such tears, woman, as you shed when you heard the cries of your dying babe. For, sir, he was a man,—and you are but another man. And, woman, though dressed in silk and jewels, you are but a woman, and in life’s great straits and mighty griefs, ye feel but one sorrow!”

As passionate as I am on this topic, I could probably write a book about the hazards of reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin and evaluating it only through 21st-century sensibilities, but, fortunately, that’s already been done. David S. Reynolds’ Mightier Than the Sword: Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the Battle for America examines Uncle Tom’s Cabin within the context of religion, the temperance movement, domesticity, and other aspects of early 1850s society and culture that made the public so receptive to the novel at that time and as it was written. It also describes, in fascinating and, again, cringeworthy detail, the lasting effects of the book.

In case you are worried that I ruined the rest of my and Lucia’s mother-daughter day in Hartford by dwelling on issues of “isms” past/present/hopefully not forever, I assure you that I did not.

After our tour of The Mark Twain House (fun fact: it’s the only publicly accessible example of the Louis Tiffany design firm’s work still in existence), Lucia and I took the advice of Yankee magazine and dined at Sparrow Pizza Bar. We were sad at the lack of sparrows, but delighted in the “not your average pizza” and vibrant bar scene. I attempted to photograph my food (bruschetta with ricotta, butternut squash, rosemary, and honey: simply deeeelicious) and the vibrant bar scene but failed miserably at both. Take my word for it and eat, drink, and be merry at Sparrow Pizza Bar, a mere three miles down Farmington Avenue from The Twain House.

After our meal, we walked around the charming West Hartford shopping district, then stumbled upon more roses, this time at Elizabeth Park. Our nation’s first municipal rose garden and, at 2.5 acres, the third largest in the country, the Helen S. Kaman Rose Garden at Elizabeth Park contains more than 15,000 rose bushes and 800 varieties. We had no idea this place existed and then, lucky us, we discovered it on a day that happened to be both sunny and during early rose blooming season. Lucia and I were pretty proud of ourselves as we scampered around the park in the sunshine: we’d fled Boston that morning in search of good weather, and we’d found that and a whole lot more in Hartford.

Alas, our hubris bit us in the ass. Literally the moment we drove over the Connecticut border into Massachusetts that evening, the clouds opened and the weather gods rained down their contempt upon us.

And did you ever have that conversation with Lucia?